Next: References and further reading

Up: Postings file compression

Previous: Variable byte codes

Contents

Index

Gamma codes

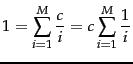

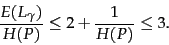

Table 5.5:

Some examples of unary and  codes.

Unary codes are only shown for the smaller numbers.

Commas in

codes.

Unary codes are only shown for the smaller numbers.

Commas in  codes are for readability only and are not part of the actual codes.

codes are for readability only and are not part of the actual codes.

| | number |

unary code |

length |

offset |

code code |

|

| | 0 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

| | 1 |

10 |

0 |

|

0 |

|

| | 2 |

110 |

10 |

0 |

10,0 |

|

| | 3 |

1110 |

10 |

1 |

10,1 |

|

| | 4 |

11110 |

110 |

00 |

110,00 |

|

| | 9 |

1111111110 |

1110 |

001 |

1110,001 |

|

| | 13 |

|

1110 |

101 |

1110,101 |

|

| | 24 |

|

11110 |

1000 |

11110,1000 |

|

| | 511 |

|

111111110 |

11111111 |

111111110,11111111 |

|

| | 1025 |

|

11111111110 |

0000000001 |

11111111110,0000000001 |

|

VB codes use an adaptive number of bytes

depending on the size of the gap. Bit-level codes adapt the

length of the code on the finer grained bit level.

The simplest bit-level code is unary code . The unary

code of  is a string of

is a string of  1s followed by a 0 (see the

first two columns of Table 5.5 ).

Obviously,

this is not a very efficient code, but it will come in handy

in a moment.

1s followed by a 0 (see the

first two columns of Table 5.5 ).

Obviously,

this is not a very efficient code, but it will come in handy

in a moment.

How efficient can a code be in principle? Assuming the

gaps

gaps  with

with

are all equally

likely, the optimal encoding uses

are all equally

likely, the optimal encoding uses  bits for each

bits for each  . So

some gaps (

. So

some gaps ( in this case) cannot be encoded with

fewer than

in this case) cannot be encoded with

fewer than  bits. Our goal is to get as close to

this lower bound as possible.

bits. Our goal is to get as close to

this lower bound as possible.

A method that is within a factor of optimal

is  encoding .

encoding .

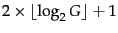

codes implement variable-length encoding by splitting the

representation of a

gap

codes implement variable-length encoding by splitting the

representation of a

gap  into a pair of length and offset.

Offset is

into a pair of length and offset.

Offset is  in binary, but with the leading 1

removed.

in binary, but with the leading 1

removed.![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png) For example, for 13 (binary 1101) offset is 101.

Length encodes the length of offset

in unary code.

For 13,

the length of offset is 3 bits, which is 1110 in

unary. The

For example, for 13 (binary 1101) offset is 101.

Length encodes the length of offset

in unary code.

For 13,

the length of offset is 3 bits, which is 1110 in

unary. The  code of 13 is therefore 1110101, the

concatenation of length 1110 and offset 101.

The right hand column of Table 5.5 gives additional

examples of

code of 13 is therefore 1110101, the

concatenation of length 1110 and offset 101.

The right hand column of Table 5.5 gives additional

examples of  codes.

codes.

A  code is decoded by first reading the unary code

up to the 0 that terminates it, for example, the four bits 1110

when decoding 1110101. Now we know how long the

offset is: 3 bits. The offset 101 can then be read correctly and

the 1 that was chopped off in encoding is prepended: 101

code is decoded by first reading the unary code

up to the 0 that terminates it, for example, the four bits 1110

when decoding 1110101. Now we know how long the

offset is: 3 bits. The offset 101 can then be read correctly and

the 1 that was chopped off in encoding is prepended: 101

1101 = 13.

1101 = 13.

The length of offset is

bits and the length of length

is

bits and the length of length

is

bits,

so the length of the entire

code is

bits,

so the length of the entire

code is

bits.

bits.  codes are

always of odd length and they are within a factor of

2 of what we claimed to be

the optimal encoding length

codes are

always of odd length and they are within a factor of

2 of what we claimed to be

the optimal encoding length  .

We derived this optimum

from the assumption

that the

.

We derived this optimum

from the assumption

that the  gaps

between

gaps

between  and

and  are equiprobable.

But this need not be the case. In general, we do not know the

probability distribution over gaps a priori.

are equiprobable.

But this need not be the case. In general, we do not know the

probability distribution over gaps a priori.

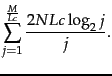

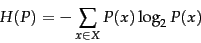

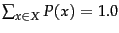

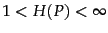

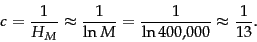

Figure 5.9:

Entropy  as a function of

as a function of  for a sample space

with two outcomes

for a sample space

with two outcomes  and

and  .

.

![\includegraphics[width=7cm]{art/entropy.eps}](img293.png) |

The characteristic of a discrete probability

distribution![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png)

that

determines its coding properties (including whether a code is

optimal) is its

entropy

that

determines its coding properties (including whether a code is

optimal) is its

entropy  , which is

defined as follows:

, which is

defined as follows:

|

(4) |

where  is the set of all possible numbers we need to be

able to encode

(and therefore

is the set of all possible numbers we need to be

able to encode

(and therefore

). Entropy is a

measure of uncertainty as shown in Figure 5.9 for a

probability distribution

). Entropy is a

measure of uncertainty as shown in Figure 5.9 for a

probability distribution  over two possible outcomes, namely,

over two possible outcomes, namely,

. Entropy is maximized (

. Entropy is maximized ( ) for

) for

when uncertainty about which

when uncertainty about which  will appear next is largest; and minimized (

will appear next is largest; and minimized ( ) for

) for

and for

and for

when there is absolute certainty.

when there is absolute certainty.

It can be shown

that the lower bound for the expected length  of a

code

of a

code  is

is  if certain conditions hold (see the references). It can

further be shown that for

if certain conditions hold (see the references). It can

further be shown that for

,

,  encoding is within a factor of 3 of this optimal encoding,

approaching 2 for large

encoding is within a factor of 3 of this optimal encoding,

approaching 2 for large  :

:

|

(5) |

What is remarkable about this result is that it holds for

any probability distribution  . So without knowing

anything about the properties of the distribution of gaps,

we can apply

. So without knowing

anything about the properties of the distribution of gaps,

we can apply  codes and be certain that they are within a

factor of

codes and be certain that they are within a

factor of  of the optimal code for distributions

of large entropy. A code like

of the optimal code for distributions

of large entropy. A code like  code with the property of

being within a factor of optimal for an arbitrary distribution

code with the property of

being within a factor of optimal for an arbitrary distribution  is

called

universal .

is

called

universal .

In addition to universality,

codes have two other properties that are useful for index

compression. First, they are

prefix free , namely, no

codes have two other properties that are useful for index

compression. First, they are

prefix free , namely, no

code is the prefix of another. This means that

there is always a unique decoding of a sequence of

code is the prefix of another. This means that

there is always a unique decoding of a sequence of

codes - and we do not need delimiters between them,

which would decrease the efficiency of the code. The second

property is that

codes - and we do not need delimiters between them,

which would decrease the efficiency of the code. The second

property is that  codes are

parameter free . For many other efficient codes, we

have to fit the parameters of a model (e.g., the

binomial distribution) to

the distribution of gaps in the index. This complicates the

implementation of compression and decompression.

For instance, the

parameters need to be stored and retrieved. And in dynamic indexing, the distribution of

gaps can change, so that the original parameters are no longer

appropriate. These problems are avoided with a

parameter-free code.

codes are

parameter free . For many other efficient codes, we

have to fit the parameters of a model (e.g., the

binomial distribution) to

the distribution of gaps in the index. This complicates the

implementation of compression and decompression.

For instance, the

parameters need to be stored and retrieved. And in dynamic indexing, the distribution of

gaps can change, so that the original parameters are no longer

appropriate. These problems are avoided with a

parameter-free code.

How much compression of the inverted index do  codes

achieve? To answer this question we use Zipf's law, the term

distribution model introduced in Section 5.1.2 .

According to Zipf's law, the collection frequency

codes

achieve? To answer this question we use Zipf's law, the term

distribution model introduced in Section 5.1.2 .

According to Zipf's law, the collection frequency  is proportional to the

inverse of the rank

is proportional to the

inverse of the rank  , that is, there is a constant

, that is, there is a constant  such that:

such that:

|

|

|

(6) |

We can choose a different constant  such that the

fractions

such that the

fractions  are relative

frequencies and sum to 1 (that is,

are relative

frequencies and sum to 1 (that is,

):

):

where  is the number of distinct terms and

is the number of distinct terms and  is the

is the

th harmonic

number .

th harmonic

number .

![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png) Reuters-RCV1 has

Reuters-RCV1 has

distinct terms

and

distinct terms

and

, so we have

, so we have

|

(9) |

Thus the  th term has a relative frequency of roughly

th term has a relative frequency of roughly

, and

the expected average number of occurrences of term

, and

the expected average number of occurrences of term

in a document of length

in a document of length  is:

is:

|

(10) |

where we interpret the relative frequency as a term occurrence

probability. Recall that 200 is the average number of

tokens per document in Reuters-RCV1 (Table 4.2 ).

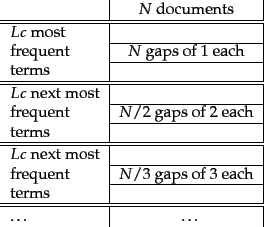

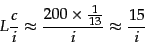

Figure 5.10:

Stratification of terms for

estimating the size of a  encoded inverted index.

encoded inverted index.

|

Now we have derived term

statistics that characterize the distribution of terms in

the collection and, by extension, the distribution of gaps in

the postings lists.

From these statistics, we can

calculate

the space requirements for an inverted index compressed with

encoding. We first stratify the

vocabulary into blocks of size

encoding. We first stratify the

vocabulary into blocks of size

.

On average, term

.

On average, term  occurs

occurs  times per

document. So the average number of occurrences

times per

document. So the average number of occurrences

per document

is

per document

is

for terms in the

first block, corresponding to a total number of

for terms in the

first block, corresponding to a total number of  gaps per

term. The average is

gaps per

term. The average is

for terms in the

second block, corresponding to

for terms in the

second block, corresponding to  gaps per term, and

gaps per term, and

for terms in the

third block, corresponding to

for terms in the

third block, corresponding to  gaps per term, and so on. (We

take the lower bound because it simplifies subsequent calculations.

As we will see, the final estimate is too

pessimistic, even with this assumption.)

We will make the somewhat unrealistic assumption that all

gaps for a given term have the same size

as shown in Figure 5.10.

Assuming such a uniform distribution of gaps,

we then have gaps of size 1 in block 1, gaps of size 2 in

block 2, and so on.

gaps per term, and so on. (We

take the lower bound because it simplifies subsequent calculations.

As we will see, the final estimate is too

pessimistic, even with this assumption.)

We will make the somewhat unrealistic assumption that all

gaps for a given term have the same size

as shown in Figure 5.10.

Assuming such a uniform distribution of gaps,

we then have gaps of size 1 in block 1, gaps of size 2 in

block 2, and so on.

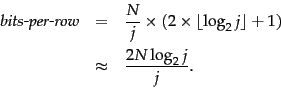

Encoding the  gaps of size

gaps of size  with

with  codes, the number of

bits needed for the postings list

of a term in the

codes, the number of

bits needed for the postings list

of a term in the  th block (corresponding to one row in

the figure) is:

th block (corresponding to one row in

the figure) is:

To encode the entire block, we need

bits. There are

bits. There are  blocks, so the postings file as a whole will

take up:

blocks, so the postings file as a whole will

take up:

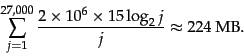

| |

|

|

(11) |

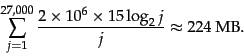

For Reuters-RCV1,

400,000

400,000

and

and

|

(12) |

So the postings file of the compressed inverted index

for our 960 MB collection has a size of 224 MB, one fourth the

size of

the original collection.

When we run  compression on Reuters-RCV1,

the actual size of the compressed index is even

lower: 101 MB, a bit more than one tenth of the size of the

collection. The reason for the discrepancy between

predicted and actual value is

that (i) Zipf's law is not a very good

approximation of the actual distribution of term frequencies

for Reuters-RCV1 and (ii) gaps are not uniform. The Zipf model predicts an index size of 251 MB

for the unrounded numbers from Table 4.2 . If

term frequencies are generated from the Zipf model and a

compressed index is created for these artificial terms, then

the compressed size is 254 MB. So to the extent that

the assumptions about the distribution of term frequencies

are accurate,

the predictions of the model are correct.

compression on Reuters-RCV1,

the actual size of the compressed index is even

lower: 101 MB, a bit more than one tenth of the size of the

collection. The reason for the discrepancy between

predicted and actual value is

that (i) Zipf's law is not a very good

approximation of the actual distribution of term frequencies

for Reuters-RCV1 and (ii) gaps are not uniform. The Zipf model predicts an index size of 251 MB

for the unrounded numbers from Table 4.2 . If

term frequencies are generated from the Zipf model and a

compressed index is created for these artificial terms, then

the compressed size is 254 MB. So to the extent that

the assumptions about the distribution of term frequencies

are accurate,

the predictions of the model are correct.

Table:

Index and dictionary compression for Reuters-RCV1.

The compression ratio depends on the proportion of actual text

in the collection. Reuters-RCV1 contains a

large amount of XML

markup. Using the two best

compression schemes,  encoding and blocking with

front coding, the

ratio compressed index to collection size is therefore

especially small for Reuters-RCV1:

encoding and blocking with

front coding, the

ratio compressed index to collection size is therefore

especially small for Reuters-RCV1:

.

.

.

.

| | data structure |

size in MB |

| | dictionary, fixed-width |

19.211.2 |

| | dictionary, term pointers into string |

10.8 7.6 |

| |  , with blocking, , with blocking,  |

10.3 7.1 |

| |  , with blocking & front coding , with blocking & front coding |

7.9 5.9 |

| | collection (text, xml markup etc) |

3600.0 |

| | collection (text) |

960.0 |

| | term incidence matrix |

40,000.0 |

| | postings, uncompressed (32-bit words) |

400.0 |

| | postings, uncompressed (20 bits) |

250.0 |

| | postings, variable byte encoded |

116.0 |

| | postings,  encoded encoded |

101.0 |

Table 5.6 summarizes

the compression techniques covered in this chapter.

The

term incidence matrix

(Figure 1.1 , page 1.1 )

for Reuters-RCV1 has size

bits or 40 GB.

The numbers were the collection (3600 MB and 960 MB) are for

the encoding of RCV1 of CD, which uses one byte per

character, not Unicode.

bits or 40 GB.

The numbers were the collection (3600 MB and 960 MB) are for

the encoding of RCV1 of CD, which uses one byte per

character, not Unicode.

codes achieve great compression ratios - about

15% better than variable byte codes for Reuters-RCV1. But they

are expensive to decode. This is because many

bit-level operations - shifts and masks - are necessary to

decode a sequence of

codes achieve great compression ratios - about

15% better than variable byte codes for Reuters-RCV1. But they

are expensive to decode. This is because many

bit-level operations - shifts and masks - are necessary to

decode a sequence of  codes as the boundaries between

codes will usually be somewhere in the middle of a machine

word. As a result, query processing is more expensive for

codes as the boundaries between

codes will usually be somewhere in the middle of a machine

word. As a result, query processing is more expensive for

codes than for variable byte codes.

Whether we choose variable byte or

codes than for variable byte codes.

Whether we choose variable byte or  encoding

depends on the characteristics of an application, for example,

on the relative

weights we give to conserving disk space versus maximizing query

response time.

encoding

depends on the characteristics of an application, for example,

on the relative

weights we give to conserving disk space versus maximizing query

response time.

The compression ratio for the index in

Table 5.6 is about 25%: 400 MB

(uncompressed, each posting stored as a 32-bit word) versus 101 MB

( ) and

116 MB (VB). This shows that both

) and

116 MB (VB). This shows that both  and VB codes meet

the objectives we stated in the beginning of the chapter.

Index compression substantially improves time and space

efficiency of indexes by reducing the amount of disk space needed,

increasing the amount of information that can be kept in

the cache, and speeding up data transfers from disk to memory.

and VB codes meet

the objectives we stated in the beginning of the chapter.

Index compression substantially improves time and space

efficiency of indexes by reducing the amount of disk space needed,

increasing the amount of information that can be kept in

the cache, and speeding up data transfers from disk to memory.

Exercises.

- Compute variable byte codes for the numbers in

Tables 5.3 5.5 .

- Compute variable byte and

codes for

the

postings list

codes for

the

postings list

777, 17743, 294068, 31251336

777, 17743, 294068, 31251336 . Use gaps instead

of docIDs where possible. Write binary codes in 8-bit blocks.

. Use gaps instead

of docIDs where possible. Write binary codes in 8-bit blocks.

-

Consider the postings list

with a corresponding list of gaps

with a corresponding list of gaps

.

Assume that the length of the postings list is stored separately, so the system knows when a postings list is complete.

Using variable byte encoding:

(i) What is the largest gap you can encode in 1 byte?

(ii) What is the largest gap you can encode in 2 bytes?

(iii) How many bytes will the above postings list require under this encoding? (Count only space for encoding the sequence of numbers.)

.

Assume that the length of the postings list is stored separately, so the system knows when a postings list is complete.

Using variable byte encoding:

(i) What is the largest gap you can encode in 1 byte?

(ii) What is the largest gap you can encode in 2 bytes?

(iii) How many bytes will the above postings list require under this encoding? (Count only space for encoding the sequence of numbers.)

- A little trick is to notice that a gap cannot be of length 0

and that the stuff left to encode after shifting cannot be

0. Based on these observations:

(i) Suggest a modification to variable byte encoding that

allows you to encode slightly larger gaps in the same amount

of space.

(ii) What is the largest gap you can encode in 1 byte?

(iii) What is the largest gap you can encode in 2 bytes?

(iv) How many bytes will the postings list in Exercise 5.3.2

require under this encoding?

(Count only space for encoding the sequence of numbers.)

- From the following sequence of

-coded gaps,

reconstruct first the gap sequence and then the postings

sequence: 1110001110101011111101101111011.

-coded gaps,

reconstruct first the gap sequence and then the postings

sequence: 1110001110101011111101101111011.

-

codes are relatively

inefficient for large numbers (e.g., 1025 in

Table 5.5 ) as they encode the length of the

offset in inefficient unary code.

codes are relatively

inefficient for large numbers (e.g., 1025 in

Table 5.5 ) as they encode the length of the

offset in inefficient unary code.  codes

differ from

codes

differ from  codes in that they encode the first

part of the code (length) in

codes in that they encode the first

part of the code (length) in  code instead of

unary code. The encoding of offset is the

same. For example, the

code instead of

unary code. The encoding of offset is the

same. For example, the  code of 7 is 10,0,11 (again,

we add commas for readability). 10,0 is the

code of 7 is 10,0,11 (again,

we add commas for readability). 10,0 is the  code

for length (2 in this case) and the encoding of offset

(11) is unchanged. (i) Compute the

code

for length (2 in this case) and the encoding of offset

(11) is unchanged. (i) Compute the  codes for the other

numbers in Table 5.5 . For what range of numbers

is the

codes for the other

numbers in Table 5.5 . For what range of numbers

is the  code shorter than the

code shorter than the  code?

(ii)

code?

(ii)  code beats variable byte code in

Table 5.6 because the index contains stop words and thus

many small gaps. Show that variable byte code is more

compact if larger gaps dominate. (iii) Compare the

compression ratios of

code beats variable byte code in

Table 5.6 because the index contains stop words and thus

many small gaps. Show that variable byte code is more

compact if larger gaps dominate. (iii) Compare the

compression ratios of  code and variable byte code

for a distribution of gaps dominated by large gaps.

code and variable byte code

for a distribution of gaps dominated by large gaps.

- Go through the above calculation of index size and

explicitly state all the approximations that were made to

arrive at Equation 11.

- For a collection of your choosing, determine the number

of documents and terms and the average length of a

document. (i) How large is the inverted index predicted to be by

Equation 11? (ii) Implement an indexer that

creates a

-compressed inverted index for the

collection. How large is the actual index? (iii) Implement an

indexer that uses variable byte encoding. How large is the

variable byte encoded index?

-compressed inverted index for the

collection. How large is the actual index? (iii) Implement an

indexer that uses variable byte encoding. How large is the

variable byte encoded index?

Table:

Two gap sequences to be merged in blocked sort-based indexing

| |  encoded gap sequence of run 1 encoded gap sequence of run 1 |

1110110111111001011111111110100011111001 |

|

| |  encoded gap sequence of run 2 encoded gap sequence of run 2 |

11111010000111111000100011111110010000011111010101

|

|

- To be able to hold as many postings as possible in

main memory, it is a good idea to compress intermediate

index files during index construction. (i) This makes

merging runs in blocked sort-based indexing more complicated. As an

example, work out the

-encoded merged sequence of

the gaps in Table 5.7 . (ii) Index construction is

more space efficient when using compression. Would you also

expect it to be faster?

-encoded merged sequence of

the gaps in Table 5.7 . (ii) Index construction is

more space efficient when using compression. Would you also

expect it to be faster?

- (i) Show that the size of the vocabulary is finite

according to Zipf's law and infinite according to Heaps'

law. (ii) Can we derive Heaps' law from Zipf's law?

Next: References and further reading

Up: Postings file compression

Previous: Variable byte codes

Contents

Index

© 2008 Cambridge University Press

This is an automatically generated page. In case of formatting errors you may want to look at the PDF edition of the book.

2009-04-07

![\includegraphics[width=7cm]{art/entropy.eps}](img293.png)