|

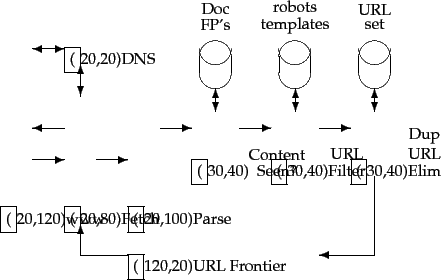

The simple scheme outlined above for crawling demands several modules that fit together as shown in Figure 20.1 .

Crawling is performed by anywhere from one to potentially hundreds of threads, each of which loops through the logical cycle in Figure 20.1 . These threads may be run in a single process, or be partitioned amongst multiple processes running at different nodes of a distributed system. We begin by assuming that the URL frontier is in place and non-empty and defer our description of the implementation of the URL frontier to Section 20.2.3 . We follow the progress of a single URL through the cycle of being fetched, passing through various checks and filters, then finally (for continuous crawling) being returned to the URL frontier.

A crawler thread begins by taking a URL from the frontier and fetching the web page at that URL, generally using the http protocol. The fetched page is then written into a temporary store, where a number of operations are performed on it. Next, the page is parsed and the text as well as the links in it are extracted. The text (with any tag information - e.g., terms in boldface) is passed on to the indexer. Link information including anchor text is also passed on to the indexer for use in ranking in ways that are described in Chapter 21 . In addition, each extracted link goes through a series of tests to determine whether the link should be added to the URL frontier.

First, the thread tests whether a web page with the same content has already been seen at another URL. The simplest implementation for this would use a simple fingerprint such as a checksum (placed in a store labeled "Doc FP's" in Figure 20.1 ). A more sophisticated test would use shingles instead of fingerprints, as described in Chapter 19 .

Next, a URL filter is used to determine whether the extracted URL should be excluded from the frontier based on one of several tests. For instance, the crawl may seek to exclude certain domains (say, all .com URLs) - in this case the test would simply filter out the URL if it were from the .com domain. A similar test could be inclusive rather than exclusive. Many hosts on the Web place certain portions of their websites off-limits to crawling, under a standard known as the Robots Exclusion Protocol , except for the robot called ``searchengine''.

User-agent: * Disallow: /yoursite/temp/ User-agent: searchengine Disallow:

The robots.txt file must be fetched from a website in order to test whether the URL under consideration passes the robot restrictions, and can therefore be added to the URL frontier. Rather than fetch it afresh for testing on each URL to be added to the frontier, a cache can be used to obtain a recently fetched copy of the file for the host. This is especially important since many of the links extracted from a page fall within the host from which the page was fetched and therefore can be tested against the host's robots.txt file. Thus, by performing the filtering during the link extraction process, we would have especially high locality in the stream of hosts that we need to test for robots.txt files, leading to high cache hit rates. Unfortunately, this runs afoul of webmasters' politeness expectations. A URL (particularly one referring to a low-quality or rarely changing document) may be in the frontier for days or even weeks. If we were to perform the robots filtering before adding such a URL to the frontier, its robots.txt file could have changed by the time the URL is dequeued from the frontier and fetched. We must consequently perform robots-filtering immediately before attempting to fetch a web page. As it turns out, maintaining a cache of robots.txt files is still highly effective; there is sufficient locality even in the stream of URLs dequeued from the URL frontier.

Next, a URL should be normalized in the following sense: often the HTML encoding of a link from a web page ![]() indicates the target of that link relative to the page

indicates the target of that link relative to the page ![]() . Thus, there is a relative link encoded thus in the HTML of the page en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page:

. Thus, there is a relative link encoded thus in the HTML of the page en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page:

<a href="/wiki/Wikipedia:General_disclaimer"title="Wikipedia:Generaldisclaimer">Disclaimers</a>points to the URL http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:General_disclaimer.

Finally, the URL is checked for duplicate elimination: if the URL is already in the frontier or (in the case of a non-continuous crawl) already crawled, we do not add it to the frontier. When the URL is added to the frontier, it is assigned a priority based on which it is eventually removed from the frontier for fetching. The details of this priority queuing are in Section 20.2.3 .

Certain housekeeping tasks are typically performed by a dedicated thread. This thread is generally quiescent except that it wakes up once every few seconds to log crawl progress statistics (URLs crawled, frontier size, etc.), decide whether to terminate the crawl, or (once every few hours of crawling) checkpoint the crawl. In checkpointing, a snapshot of the crawler's state (say, the URL frontier) is committed to disk. In the event of a catastrophic crawler failure, the crawl is restarted from the most recent checkpoint.