The rank of a matrix is the number of linearly independent rows (or columns) in it; thus,

![]() . A square

. A square ![]() matrix all of whose off-diagonal entries are zero is called a diagonal matrix; its rank is equal to the number of non-zero diagonal entries. If all

matrix all of whose off-diagonal entries are zero is called a diagonal matrix; its rank is equal to the number of non-zero diagonal entries. If all ![]() diagonal entries of such a diagonal matrix are

diagonal entries of such a diagonal matrix are ![]() , it is called the identity matrix of dimension

, it is called the identity matrix of dimension ![]() and represented by

and represented by ![]() .

.

For a square

![]() matrix

matrix ![]() and a vector

and a vector ![]() that is not all zeros, the values of

that is not all zeros, the values of ![]() satisfying

satisfying

The eigenvalues of a matrix are found by solving the

characteristic equation, which is obtained by

rewriting Equation 213 in the form

![]() . The eigenvalues of

. The eigenvalues of ![]() are then the solutions of

are then the solutions of

![]() , where

, where ![]() denotes the determinant of a square matrix

denotes the determinant of a square matrix ![]() .

The equation

.

The equation

![]() is an

is an ![]() th order polynomial equation in

th order polynomial equation in ![]() and can have at most

and can have at most ![]() roots, which are the

eigenvalues of

roots, which are the

eigenvalues of ![]() . These eigenvalues can in general be complex, even if all entries of

. These eigenvalues can in general be complex, even if all entries of ![]() are real.

are real.

We now examine some further properties of eigenvalues and eigenvectors, to set up the central idea of singular value decompositions in Section 18.2 below. First, we look at the relationship between matrix-vector multiplication and eigenvalues.

Worked example.

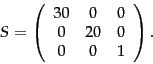

Consider the matrix

|

(215) |

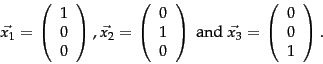

|

(216) |

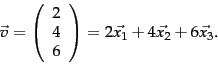

We can always express

We can always express  |

(217) |

Example 18.1 shows that even though ![]() is an arbitrary vector, the effect of multiplication by

is an arbitrary vector, the effect of multiplication by ![]() is determined by the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

is determined by the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of ![]() . Furthermore, it is intuitively apparent from Equation 221 that the product

. Furthermore, it is intuitively apparent from Equation 221 that the product ![]() is relatively unaffected by terms arising from the small eigenvalues of

is relatively unaffected by terms arising from the small eigenvalues of ![]() ; in our example, since

; in our example, since ![]() , the contribution of the third term on the right hand side of Equation 221 is small. In fact, if we were to completely ignore the contribution in Equation 221 from the third eigenvector corresponding to

, the contribution of the third term on the right hand side of Equation 221 is small. In fact, if we were to completely ignore the contribution in Equation 221 from the third eigenvector corresponding to ![]() , then the product

, then the product ![]() would be computed to be

would be computed to be

rather than the correct product which is

rather than the correct product which is

; these two vectors are relatively close to each other by any of various metrics one could apply (such as the length of their vector difference).

; these two vectors are relatively close to each other by any of various metrics one could apply (such as the length of their vector difference).

This suggests that the effect of small eigenvalues (and their eigenvectors) on a matrix-vector product is small. We will carry forward this intuition when studying matrix decompositions and low-rank approximations in Section 18.2 . Before doing so, we examine the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of special forms of matrices that will be of particular interest to us.

For a symmetric matrix ![]() , the eigenvectors corresponding to distinct eigenvalues are orthogonal. Further, if

, the eigenvectors corresponding to distinct eigenvalues are orthogonal. Further, if ![]() is both real and symmetric, the eigenvalues are all real.

is both real and symmetric, the eigenvalues are all real.

Worked example.

Consider the real, symmetric matrix

and

and

are orthogonal.

End worked example.

are orthogonal.

End worked example.