Digital documents that are the input to an indexing process are typically

bytes in a file or on a web server. The first step of processing is to

convert this byte sequence into a linear sequence of characters. For the

case of plain English text in ASCII encoding, this is

trivial. But often things get much more complex. The sequence of

characters may be encoded by one of various single byte or multibyte

encoding schemes,

such as Unicode UTF-8, or various national or vendor-specific

standards. We need to determine the correct encoding. This can be

regarded as a machine learning

classification problem, as discussed

in Chapter 13 ,![]() but is often handled by heuristic methods, user

selection, or by using provided document metadata.

Once the encoding is

determined, we decode the byte sequence to a

character sequence. We might save the choice of encoding

because it gives some evidence about what language the document is

written in.

but is often handled by heuristic methods, user

selection, or by using provided document metadata.

Once the encoding is

determined, we decode the byte sequence to a

character sequence. We might save the choice of encoding

because it gives some evidence about what language the document is

written in.

The characters may have to be decoded out of some binary representation like Microsoft Word DOC files and/or a compressed format such as zip files. Again, we must determine the document format, and then an appropriate decoder has to be used. Even for plain text documents, additional decoding may need to be done. In XML documents xmlbasic, character entities, such as &, need to be decoded to give the correct character, namely & for &. Finally, the textual part of the document may need to be extracted out of other material that will not be processed. This might be the desired handling for XML files, if the markup is going to be ignored; we would almost certainly want to do this with postscript or PDF files. We will not deal further with these issues in this book, and will assume henceforth that our documents are a list of characters. Commercial products usually need to support a broad range of document types and encodings, since users want things to just work with their data as is. Often, they just think of documents as text inside applications and are not even aware of how it is encoded on disk. This problem is usually solved by licensing a software library that handles decoding document formats and character encodings.

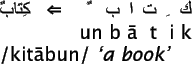

The idea that text is a linear sequence of characters is also called into question by some writing systems, such as Arabic, where text takes on some two dimensional and mixed order characteristics, as shown in and 2.2 . But, despite some complicated writing system conventions, there is an underlying sequence of sounds being represented and hence an essentially linear structure remains, and this is what is represented in the digital representation of Arabic, as shown in Figure 2.1 .

An example of a vocalized Modern

Standard Arabic word.The writing is from right to left and letters

undergo complex mutations as they are combined. The

representation of short vowels (here, /i/ and /u/) and the final /n/

(nunation) departs from strict linearity by being represented as

diacritics above and below letters. Nevertheless, the represented

text is still clearly a linear ordering of characters representing

sounds. Full vocalization, as here, normally appears only in the

Koran and children's books. Day-to-day text is unvocalized (short

vowels are not represented but the letter for a would still

appear) or partially vocalized, with short vowels inserted

in places where the writer perceives ambiguities. These choices add

further complexities to indexing.

An example of a vocalized Modern

Standard Arabic word.The writing is from right to left and letters

undergo complex mutations as they are combined. The

representation of short vowels (here, /i/ and /u/) and the final /n/

(nunation) departs from strict linearity by being represented as

diacritics above and below letters. Nevertheless, the represented

text is still clearly a linear ordering of characters representing

sounds. Full vocalization, as here, normally appears only in the

Koran and children's books. Day-to-day text is unvocalized (short

vowels are not represented but the letter for a would still

appear) or partially vocalized, with short vowels inserted

in places where the writer perceives ambiguities. These choices add

further complexities to indexing.

![\includegraphics[width=4.5in]{Arabic-bidirectional.eps}](img73.png) The conceptual linear order of characters is not necessarily

the order that you see on the page.

In languages that are written right-to-left, such as Hebrew and Arabic,

it is quite common to also have left-to-right text interspersed, such

as numbers and dollar amounts.

With modern Unicode representation concepts, the order of characters

in files matches the

conceptual order, and the reversal of displayed characters is handled

by the rendering system, but this may not be true for documents in

older encodings.

The conceptual linear order of characters is not necessarily

the order that you see on the page.

In languages that are written right-to-left, such as Hebrew and Arabic,

it is quite common to also have left-to-right text interspersed, such

as numbers and dollar amounts.

With modern Unicode representation concepts, the order of characters

in files matches the

conceptual order, and the reversal of displayed characters is handled

by the rendering system, but this may not be true for documents in

older encodings.