Next: Types of language models

Up: Language models

Previous: Language models

Contents

Index

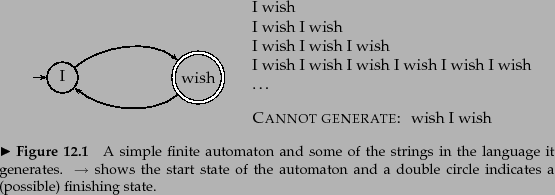

What do we mean by a document model generating a query? A traditional

generative model of a language, of the kind familiar from formal

language theory, can be used either to recognize or to generate strings.

For example, the finite automaton shown in Figure 12.1 can generate

strings that include the examples shown. The full set of strings that

can be generated is called the language of the

automaton.![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png)

If instead each node has a probability distribution over generating

different terms, we have a language model. The notion of a language model is inherently probabilistic. A language model

is a function that puts a

probability measure over strings drawn from some vocabulary. That is, for

a language model  over an alphabet

over an alphabet  :

:

|

(90) |

One simple kind of language model is equivalent to a probabilistic

finite automaton consisting of just a single node

with a single probability distribution over producing different terms,

so that

, as

shown in Figure 12.2 . After generating each word, we decide whether

to stop or to loop around and then produce another word, and so the

model also requires a probability of stopping in the

finishing state. Such a model places a probability distribution

over any sequence of words. By construction, it also provides a model

for generating text according to its distribution.

, as

shown in Figure 12.2 . After generating each word, we decide whether

to stop or to loop around and then produce another word, and so the

model also requires a probability of stopping in the

finishing state. Such a model places a probability distribution

over any sequence of words. By construction, it also provides a model

for generating text according to its distribution.

Worked example. To find the

probability of a word sequence, we just multiply the probabilities

which the model gives to each word in the sequence, together with the

probability of continuing or stopping after producing each word. For example,

As you can see, the probability of a particular string/document, is usually a

very small number! Here we stopped after generating frog the

second time. The

first line of numbers are the term emission probabilities, and the

second line gives the probability of continuing or stopping after

generating each word. An explicit

stop probability is needed for a finite automaton to be a well-formed

language model according to Equation 90. Nevertheless, most

of the time, we will omit to include STOP and

probabilities (as do most

other authors). To compare two models for a data set, we can

calculate their likelihood ratio , which results from simply dividing

the probability of the data according to one model by the probability

of the data according to the other model.

Providing that the stop probability is

fixed, its inclusion will not alter the likelihood ratio that results

from comparing the likelihood of two language models generating

a string. Hence, it will not alter the ranking of documents.

probabilities (as do most

other authors). To compare two models for a data set, we can

calculate their likelihood ratio , which results from simply dividing

the probability of the data according to one model by the probability

of the data according to the other model.

Providing that the stop probability is

fixed, its inclusion will not alter the likelihood ratio that results

from comparing the likelihood of two language models generating

a string. Hence, it will not alter the ranking of documents.![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png) Nevertheless, formally, the numbers will no longer truly be

probabilities, but only proportional to probabilities. See

Exercise 12.1.3 .

End worked example.

Nevertheless, formally, the numbers will no longer truly be

probabilities, but only proportional to probabilities. See

Exercise 12.1.3 .

End worked example.

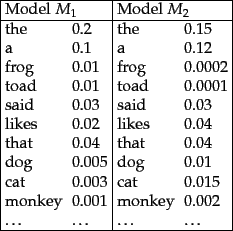

Figure 12.3:

Partial specification of two unigram language

models.

|

Worked example. Suppose, now, that we have two language models  and

and  , shown

partially in Figure 12.3 . Each gives a probability estimate to a

sequence of terms, as already illustrated in m1probability.

The language model that

gives the higher probability to the sequence of terms is more likely to

have generated the term sequence. This time, we will omit

STOP probabilities from our calculations.

For the sequence shown, we get:

, shown

partially in Figure 12.3 . Each gives a probability estimate to a

sequence of terms, as already illustrated in m1probability.

The language model that

gives the higher probability to the sequence of terms is more likely to

have generated the term sequence. This time, we will omit

STOP probabilities from our calculations.

For the sequence shown, we get:

![\begin{example}

\begin{tabular}[t]{lllllllll}

$s$\ & frog & said & that & toad &...

...column{5}{l}{$P(s\vert M_2) = 0.000000000000000384 $}

\end{tabular}\end{example}](img805.png)

and we see that

.

We present the formulas here in terms of products of probabilities,

but, as is common in probabilistic applications, in practice it is

usually best to work with sums of log probabilities (cf. page 13.2 ).

End worked example.

.

We present the formulas here in terms of products of probabilities,

but, as is common in probabilistic applications, in practice it is

usually best to work with sums of log probabilities (cf. page 13.2 ).

End worked example.

Next: Types of language models

Up: Language models

Previous: Language models

Contents

Index

© 2008 Cambridge University Press

This is an automatically generated page. In case of formatting errors you may want to look at the PDF edition of the book.

2009-04-07

![]()

![]() over an alphabet

over an alphabet ![]() :

:

![]() and

and ![]() , shown

partially in Figure 12.3 . Each gives a probability estimate to a

sequence of terms, as already illustrated in m1probability.

The language model that

gives the higher probability to the sequence of terms is more likely to

have generated the term sequence. This time, we will omit

STOP probabilities from our calculations.

For the sequence shown, we get:

, shown

partially in Figure 12.3 . Each gives a probability estimate to a

sequence of terms, as already illustrated in m1probability.

The language model that

gives the higher probability to the sequence of terms is more likely to

have generated the term sequence. This time, we will omit

STOP probabilities from our calculations.

For the sequence shown, we get:

![\begin{example}

\begin{tabular}[t]{lllllllll}

$s$\ & frog & said & that & toad &...

...column{5}{l}{$P(s\vert M_2) = 0.000000000000000384 $}

\end{tabular}\end{example}](img805.png)

![]() .

We present the formulas here in terms of products of probabilities,

but, as is common in probabilistic applications, in practice it is

usually best to work with sums of log probabilities (cf. page 13.2 ).

End worked example.

.

We present the formulas here in terms of products of probabilities,

but, as is common in probabilistic applications, in practice it is

usually best to work with sums of log probabilities (cf. page 13.2 ).

End worked example.