![\begin{figure}\begin{pspicture}(0.5,1.5)(8.5,8.25)

\psset{arrowscale=2,dotsize=6...

...ale=2]{->}(5.3,2.3)(7.5,4.5)

\rput(6.3,2.8){$\xi_j$}

\end{pspicture}\end{figure}](img1314.png) |

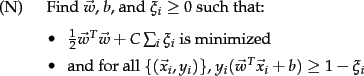

For the very high dimensional problems common in text classification, sometimes the data are linearly separable. But in the general case they are not, and even if they are, we might prefer a solution that better separates the bulk of the data while ignoring a few weird noise documents.

If the training set

![]() is not linearly separable, the

standard approach is to allow the

fat decision margin to make a few mistakes (some points - outliers

or noisy examples - are inside or on

the wrong side of the margin). We then pay a cost

for each misclassified example, which depends on how far it is from

meeting the margin requirement given in Equation 169.

To implement this, we introduce slack variables

is not linearly separable, the

standard approach is to allow the

fat decision margin to make a few mistakes (some points - outliers

or noisy examples - are inside or on

the wrong side of the margin). We then pay a cost

for each misclassified example, which depends on how far it is from

meeting the margin requirement given in Equation 169.

To implement this, we introduce slack variables ![]() . A

non-zero value for

. A

non-zero value for ![]() allows

allows ![]() to not meet the margin

requirement at a cost proportional to the value of

to not meet the margin

requirement at a cost proportional to the value of ![]() .

See Figure 15.5 .

.

See Figure 15.5 .

The formulation of the SVM optimization problem with slack variables is:

The optimization problem is then

trading off how fat it can make the margin versus how many points have

to be moved around to allow this margin. The margin can be less than 1

for a point ![]() by setting

by setting ![]() , but then one pays a penalty of

, but then one pays a penalty of

![]() in

the minimization for having done that.

The sum of the

in

the minimization for having done that.

The sum of the ![]() gives an upper bound on the number of training errors. Soft-margin SVMs minimize training error traded off against margin.

The parameter

gives an upper bound on the number of training errors. Soft-margin SVMs minimize training error traded off against margin.

The parameter ![]() is a

regularization term, which provides

a way to control overfitting: as

is a

regularization term, which provides

a way to control overfitting: as ![]() becomes large, it

is unattractive to not respect the data at the cost of reducing the

geometric margin; when it is small, it is easy to account for some

data points with the use of slack variables and to have a fat

margin placed so it models the bulk of the data.

becomes large, it

is unattractive to not respect the data at the cost of reducing the

geometric margin; when it is small, it is easy to account for some

data points with the use of slack variables and to have a fat

margin placed so it models the bulk of the data.

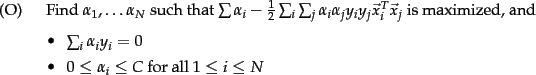

The dual problem for soft margin classification becomes:

Neither the slack variables ![]() nor Lagrange multipliers

for them appear in the dual problem. All we are left with is the

constant

nor Lagrange multipliers

for them appear in the dual problem. All we are left with is the

constant ![]() bounding the possible size of the Lagrange multipliers for

the support vector data points. As before, the

bounding the possible size of the Lagrange multipliers for

the support vector data points. As before, the ![]() with non-zero

with non-zero

![]() will be the support vectors. The solution of the dual problem is of

the form:

will be the support vectors. The solution of the dual problem is of

the form:

![]()

Again ![]() is not needed explicitly for classification, which can be

done in terms of dot products with data points, as in Equation 170.

is not needed explicitly for classification, which can be

done in terms of dot products with data points, as in Equation 170.

Typically, the support vectors will be a small proportion of the

training data. However, if the problem is non-separable or with small

margin, then every data point which is misclassified or within

the margin will have a non-zero ![]() . If this set of points

becomes large, then, for the nonlinear case which we turn to in

Section 15.2.3 , this can be a major slowdown for using SVMs at

test time.

. If this set of points

becomes large, then, for the nonlinear case which we turn to in

Section 15.2.3 , this can be a major slowdown for using SVMs at

test time.

| Classifier | Mode | Method | Time complexity |

| NB | training |

|

|

| NB | testing |

|

|

| Rocchio | training |

|

|

| Rocchio | testing |

|

|

| kNN | training | preprocessing |

|

| kNN | testing | preprocessing |

|

| kNN | training | no preprocessing | |

| kNN | testing | no preprocessing |

|

| SVM | training | conventional |

|

|

|

|||

| SVM | training | cutting planes |

|

| SVM | testing |

|

The complexity of training and testing with linear SVMs is shown in

Table 15.1 .![]() The time for training an SVM is dominated by

the time for solving the underlying QP, and so the theoretical and

empirical complexity

varies depending on the method used to solve it.

The standard result for solving QPs is that it takes time cubic

in the size of the data set (Kozlov et al., 1979). All the

recent work on SVM training has worked to reduce that complexity,

often by being satisfied with approximate solutions. Standardly, empirical

complexity is about

The time for training an SVM is dominated by

the time for solving the underlying QP, and so the theoretical and

empirical complexity

varies depending on the method used to solve it.

The standard result for solving QPs is that it takes time cubic

in the size of the data set (Kozlov et al., 1979). All the

recent work on SVM training has worked to reduce that complexity,

often by being satisfied with approximate solutions. Standardly, empirical

complexity is about

![]() (Joachims, 2006a).

Nevertheless, the super-linear training time

of traditional SVM algorithms makes them difficult or impossible to use on

very large training data sets. Alternative traditional SVM solution

algorithms which are

linear in the number of training examples scale badly with a large

number of features, which is another standard attribute of text problems.

However, a new training algorithm based on cutting plane techniques

gives a promising answer to this issue

by having running time linear in the number of training examples and the number of

non-zero features in examples (Joachims, 2006a).

Nevertheless, the actual speed of doing quadratic optimization remains

much slower than simply counting terms as is done in a Naive Bayes

model. Extending SVM

algorithms to nonlinear SVMs, as in the next section, standardly increases

training complexity by a factor of

(Joachims, 2006a).

Nevertheless, the super-linear training time

of traditional SVM algorithms makes them difficult or impossible to use on

very large training data sets. Alternative traditional SVM solution

algorithms which are

linear in the number of training examples scale badly with a large

number of features, which is another standard attribute of text problems.

However, a new training algorithm based on cutting plane techniques

gives a promising answer to this issue

by having running time linear in the number of training examples and the number of

non-zero features in examples (Joachims, 2006a).

Nevertheless, the actual speed of doing quadratic optimization remains

much slower than simply counting terms as is done in a Naive Bayes

model. Extending SVM

algorithms to nonlinear SVMs, as in the next section, standardly increases

training complexity by a factor of

![]() (since dot

products between

examples need to be calculated), making them impractical.

In practice it can often be cheaper to

materialize the higher-order features and to train a linear

SVM.

(since dot

products between

examples need to be calculated), making them impractical.

In practice it can often be cheaper to

materialize the higher-order features and to train a linear

SVM.![]()