Next: Feature selectionChi2 Feature selection

Up: Feature selection

Previous: Feature selection

Contents

Index

Mutual

information

A common feature selection method is to compute  as

the expected mutual information (MI) of term

as

the expected mutual information (MI) of term  and

class

and

class  .

.![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png) MI measures how much information the

presence/absence of a term contributes to making the correct

classification decision on

MI measures how much information the

presence/absence of a term contributes to making the correct

classification decision on  . Formally:

. Formally:

where  is a random variable that

takes values

is a random variable that

takes values  (the document contains term

(the document contains term  ) and

) and

(the document does not contain

(the document does not contain  ),

as defined on page 13.4 , and

),

as defined on page 13.4 , and  is a random variable

that takes values

is a random variable

that takes values  (the document is in class

(the document is in class  ) and

) and  (the document is not in

class

(the document is not in

class  ).

We write

).

We write  and

and  if it is not clear from context which term

if it is not clear from context which term  and class

and class  we are referring to.

we are referring to.

For

MLEs of the probabilities,

Equation 130 is equivalent to Equation 131:

where the  s are

counts of documents that have the values of

s are

counts of documents that have the values of

and

and  that are indicated by the two subscripts.

For example,

that are indicated by the two subscripts.

For example,

is the number of documents that contain

is the number of documents that contain  (

( ) and

are not in

) and

are not in  (

( ).

).

is the number of documents that

contain

is the number of documents that

contain  (

( ) and we count documents independent

of class membership (

) and we count documents independent

of class membership (

).

).

is the total number of documents. An example of one of the MLE

estimates that transform Equation 130 into Equation 131 is

is the total number of documents. An example of one of the MLE

estimates that transform Equation 130 into Equation 131 is

.

.

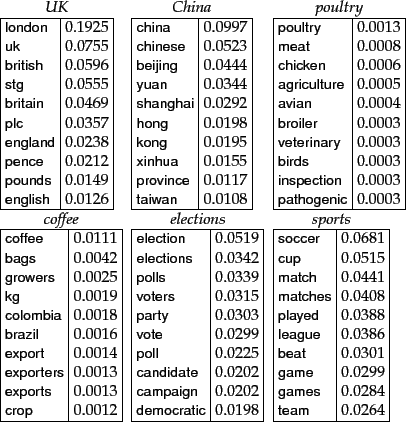

Worked example.

Consider the class poultry and the

term export in Reuters-RCV1. The counts of the

number of documents with the four possible combinations of

indicator values are as follows:

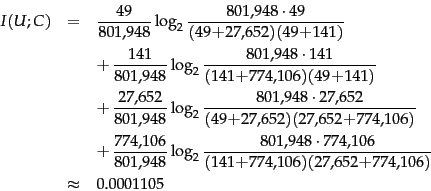

After plugging these values into Equation 131

we get:

End worked example.

To select  terms

terms

for a given class, we

use the feature selection algorithm in

Figure 13.6 : We compute the utility measure as

for a given class, we

use the feature selection algorithm in

Figure 13.6 : We compute the utility measure as

and select the

and select the  terms with the

largest values.

terms with the

largest values.

Mutual information measures how much information - in the

information-theoretic sense - a term contains about the

class. If a term's distribution is the same in the class as

it is in the collection as a whole, then

. MI

reaches its maximum value if the term is a perfect indicator

for class membership, that is, if the term is present in a document if

and only if the document is in the class.

. MI

reaches its maximum value if the term is a perfect indicator

for class membership, that is, if the term is present in a document if

and only if the document is in the class.

Figure 13.7:

Features with high

mutual information scores for six Reuters-RCV1 classes.

|

Figure 13.7 shows terms with high

mutual information scores for the six classes

in Figure 13.1 .![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png) The selected terms (e.g.,

london, uk, british for the class UK)

are of

obvious utility for making classification decisions for their respective classes.

At the bottom of the list for UK we find terms like peripherals and

tonight (not shown in the figure) that are clearly not helpful in deciding whether the

document is in the class. As you might expect, keeping the

informative terms and eliminating the non-informative ones

tends to reduce noise and improve the classifier's accuracy.

The selected terms (e.g.,

london, uk, british for the class UK)

are of

obvious utility for making classification decisions for their respective classes.

At the bottom of the list for UK we find terms like peripherals and

tonight (not shown in the figure) that are clearly not helpful in deciding whether the

document is in the class. As you might expect, keeping the

informative terms and eliminating the non-informative ones

tends to reduce noise and improve the classifier's accuracy.

Figure 13.8:

Effect of feature set size on accuracy for

multinomial and Bernoulli models.

![\includegraphics[totalheight=3in]{art/irnbayes7.eps}](img1042.png) |

Such an accuracy increase can be observed in

Figure 13.8 , which shows  as a function of

vocabulary size after feature selection for

Reuters-RCV1.

as a function of

vocabulary size after feature selection for

Reuters-RCV1.![[*]](http://nlp.stanford.edu/IR-book/html/icons/footnote.png) Comparing

Comparing

at 132,776 features (corresponding to selection of all

features) and at 10-100 features, we see that MI feature

selection increases

at 132,776 features (corresponding to selection of all

features) and at 10-100 features, we see that MI feature

selection increases  by about 0.1 for the multinomial

model and by more than 0.2 for the Bernoulli model. For the

Bernoulli model,

by about 0.1 for the multinomial

model and by more than 0.2 for the Bernoulli model. For the

Bernoulli model,  peaks early, at ten features selected.

At that point, the Bernoulli model is better than the

multinomial model. When basing a classification decision on

only a few features, it is more robust to consider binary

occurrence only. For the multinomial model (MI feature selection), the peak occurs

later, at 100 features, and its effectiveness recovers somewhat

at the end when we use all features. The reason is that the

multinomial takes the number of occurrences into account in

parameter estimation and classification and therefore better

exploits a larger number of features than the Bernoulli

model. Regardless of the differences between the two

methods, using a carefully selected subset of the features

results in better effectiveness than using all

features.

peaks early, at ten features selected.

At that point, the Bernoulli model is better than the

multinomial model. When basing a classification decision on

only a few features, it is more robust to consider binary

occurrence only. For the multinomial model (MI feature selection), the peak occurs

later, at 100 features, and its effectiveness recovers somewhat

at the end when we use all features. The reason is that the

multinomial takes the number of occurrences into account in

parameter estimation and classification and therefore better

exploits a larger number of features than the Bernoulli

model. Regardless of the differences between the two

methods, using a carefully selected subset of the features

results in better effectiveness than using all

features.

Next: Feature selectionChi2 Feature selection

Up: Feature selection

Previous: Feature selection

Contents

Index

© 2008 Cambridge University Press

This is an automatically generated page. In case of formatting errors you may want to look at the PDF edition of the book.

2009-04-07

![]() as

the expected mutual information (MI) of term

as

the expected mutual information (MI) of term ![]() and

class

and

class ![]() .

.![]() MI measures how much information the

presence/absence of a term contributes to making the correct

classification decision on

MI measures how much information the

presence/absence of a term contributes to making the correct

classification decision on ![]() . Formally:

. Formally:

![]() terms

terms

![]() for a given class, we

use the feature selection algorithm in

Figure 13.6 : We compute the utility measure as

for a given class, we

use the feature selection algorithm in

Figure 13.6 : We compute the utility measure as

![]() and select the

and select the ![]() terms with the

largest values.

terms with the

largest values.

![]() . MI

reaches its maximum value if the term is a perfect indicator

for class membership, that is, if the term is present in a document if

and only if the document is in the class.

. MI

reaches its maximum value if the term is a perfect indicator

for class membership, that is, if the term is present in a document if

and only if the document is in the class.

![]() The selected terms (e.g.,

london, uk, british for the class UK)

are of

obvious utility for making classification decisions for their respective classes.

At the bottom of the list for UK we find terms like peripherals and

tonight (not shown in the figure) that are clearly not helpful in deciding whether the

document is in the class. As you might expect, keeping the

informative terms and eliminating the non-informative ones

tends to reduce noise and improve the classifier's accuracy.

The selected terms (e.g.,

london, uk, british for the class UK)

are of

obvious utility for making classification decisions for their respective classes.

At the bottom of the list for UK we find terms like peripherals and

tonight (not shown in the figure) that are clearly not helpful in deciding whether the

document is in the class. As you might expect, keeping the

informative terms and eliminating the non-informative ones

tends to reduce noise and improve the classifier's accuracy.