| (121) | |||

|

(122) | ||

| (123) |

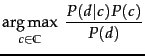

We can interpret

Equation 123 as a description of the

generative process we assume in Bayesian text

classification. To generate a document, we first choose

class ![]() with probability

with probability ![]() (top nodes in

and 13.5 ).

The two models

differ in the formalization of the second step, the

generation of the document given the class, corresponding to

the conditional distribution

(top nodes in

and 13.5 ).

The two models

differ in the formalization of the second step, the

generation of the document given the class, corresponding to

the conditional distribution

![]() :

:

It should now be clearer why we introduced the

document space

![]() in Equation 112 when we defined the classification problem.

A critical step

in solving a text classification problem

is to choose the document

representation.

in Equation 112 when we defined the classification problem.

A critical step

in solving a text classification problem

is to choose the document

representation.

![]() and

and

![]() are two different

document representations.

In the first case,

are two different

document representations.

In the first case,

![]() is the set of all term sequences (or, more

precisely, sequences of term tokens).

In the second case,

is the set of all term sequences (or, more

precisely, sequences of term tokens).

In the second case,

![]() is

is

![]() .

.

We cannot use

and 125 for text

classification directly.

For the Bernoulli model,

we would have to estimate

![]() different

parameters, one for each possible combination of

different

parameters, one for each possible combination of ![]() values

values ![]() and a class. The number of parameters

in the

multinomial case has the same order of

magnitude.

and a class. The number of parameters

in the

multinomial case has the same order of

magnitude.![]() This being a very large

quantity, estimating these parameters reliably is

infeasible.

This being a very large

quantity, estimating these parameters reliably is

infeasible.

To reduce the number of parameters,

we make

the Naive Bayes conditional independence

assumption . We assume that attribute values are independent of

each other given the class:

We illustrate the conditional independence assumption in and 13.5 . The class China generates values for each of the five term attributes (multinomial) or six binary attributes (Bernoulli) with a certain probability, independent of the values of the other attributes. The fact that a document in the class China contains the term Taipei does not make it more likely or less likely that it also contains Beijing.

In reality, the conditional independence assumption does not hold for text data. Terms are conditionally dependent on each other. But as we will discuss shortly, NB models perform well despite the conditional independence assumption.

Even when assuming conditional independence, we still have

too many parameters for the multinomial model if

we assume a different probability distribution

for each position ![]() in the

document. The position of a term in a document by itself

does not carry information about the class. Although there is a

difference between China sues France and France

sues China, the occurrence of China in position 1

versus position 3 of the document is not useful in NB

classification because we look at each term separately.

The conditional independence assumption commits

us to this way of processing the evidence.

in the

document. The position of a term in a document by itself

does not carry information about the class. Although there is a

difference between China sues France and France

sues China, the occurrence of China in position 1

versus position 3 of the document is not useful in NB

classification because we look at each term separately.

The conditional independence assumption commits

us to this way of processing the evidence.

Also, if we assumed different term distributions for each

position ![]() , we would have to estimate a different set of

parameters for each

, we would have to estimate a different set of

parameters for each ![]() . The probability of bean

appearing as the first term of a coffee document

could be different from it appearing as the second term, and

so on.

This again causes problems in estimation owing to

data sparseness.

. The probability of bean

appearing as the first term of a coffee document

could be different from it appearing as the second term, and

so on.

This again causes problems in estimation owing to

data sparseness.

For these reasons, we make a second

independence assumption for the multinomial model,

positional independence :

The conditional probabilities for a term are the same

independent of position in the document.

| (128) |

With conditional and positional independence assumptions, we only need to estimate

![]() parameters

parameters

![]() (multinomial model) or

(multinomial model) or

![]() (Bernoulli model), one for each term-class

combination, rather than a number that is at least exponential in

(Bernoulli model), one for each term-class

combination, rather than a number that is at least exponential in

![]() , the size of the vocabulary.

The independence

assumptions reduce the number of parameters to be estimated

by several orders of magnitude.

, the size of the vocabulary.

The independence

assumptions reduce the number of parameters to be estimated

by several orders of magnitude.

To summarize, we generate a document in the multinomial

model (Figure 13.4 ) by first picking a class ![]() with

with ![]() where

where ![]() is a

random variable taking values

from

is a

random variable taking values

from ![]() as values. Next we generate term

as values. Next we generate term

![]() in position

in position ![]() with

with

![]() for each of the

for each of the ![]() positions of the

document. The

positions of the

document. The ![]() all have the same

distribution over terms for a given

all have the same

distribution over terms for a given ![]() . In the example in

Figure 13.4 , we show the generation

of

. In the example in

Figure 13.4 , we show the generation

of

![]() , corresponding to

the one-sentence document

Beijing and Taipei join WTO.

, corresponding to

the one-sentence document

Beijing and Taipei join WTO.

For a completely specified document generation model, we

would also have to define a distribution

![]() over

lengths. Without it, the multinomial model is

a token generation model rather than a document

generation model.

over

lengths. Without it, the multinomial model is

a token generation model rather than a document

generation model.

We generate a document in the Bernoulli model

(Figure 13.5 ) by first picking a class ![]() with

with

![]() and then generating a binary indicator

and then generating a binary indicator ![]() for

each term

for

each term ![]() of the vocabulary

(

of the vocabulary

(

![]() ).

In the example in

Figure 13.5 , we show the generation

of

).

In the example in

Figure 13.5 , we show the generation

of

![]() , corresponding, again, to the one-sentence document

Beijing and Taipei join WTO where we have

assumed that

and is a stop word.

, corresponding, again, to the one-sentence document

Beijing and Taipei join WTO where we have

assumed that

and is a stop word.

| multinomial model | Bernoulli model | |||

| event model | generation of token | generation of document | ||

| random variable(s) |

|

|||

| document representation |

|

|

||

|

|

||||

| parameter estimation |

|

|

||

| decision rule: maximize |

|

|

||

| multiple occurrences | taken into account | ignored | ||

| length of docs | can handle longer docs | works best for short docs | ||

| # features | can handle more | works best with fewer | ||

| estimate for term the |

|

|

We compare the two models in Table 13.3 , including estimation equations and decision rules.

Naive Bayes is so called because the independence assumptions we have just made are indeed very naive for a model of natural language. The conditional independence assumption states that features are independent of each other given the class. This is hardly ever true for terms in documents. In many cases, the opposite is true. The pairs hong and kong or london and english in Figure 13.7 are examples of highly dependent terms. In addition, the multinomial model makes an assumption of positional independence. The Bernoulli model ignores positions in documents altogether because it only cares about absence or presence. This bag-of-words model discards all information that is communicated by the order of words in natural language sentences. How can NB be a good text classifier when its model of natural language is so oversimplified?

| class selected | |||||

| true probability |

0.6 | 0.4 | |||

|

|

0.00099 | 0.00001 | |||

| NB estimate |

0.99 | 0.01 |

The answer is that

even though the probability estimates of

NB are of low quality, its classification

decisions are surprisingly good. Consider a document ![]() with true probabilities

with true probabilities

![]() and

and

![]() as shown in Table 13.4 .

Assume that

as shown in Table 13.4 .

Assume that ![]() contains

many terms that are positive indicators for

contains

many terms that are positive indicators for ![]() and many terms that are negative indicators for

and many terms that are negative indicators for ![]() .

Thus, when using the

multinomial model in Equation 126,

.

Thus, when using the

multinomial model in Equation 126,

![]() will be much larger than

will be much larger than

![]() (0.00099 vs. 0.00001 in the table).

After division by 0.001 to get well-formed probabilities

for

(0.00099 vs. 0.00001 in the table).

After division by 0.001 to get well-formed probabilities

for ![]() , we end up with one estimate that is close to

1.0 and one that is close to 0.0. This is common:

The winning class in NB classification

usually has a much larger probability than the other

classes and the estimates diverge very significantly from

the true probabilities. But the

classification decision is based on which class gets the

highest score. It does not matter how accurate the

estimates are. Despite the bad estimates, NB

estimates a

higher probability for

, we end up with one estimate that is close to

1.0 and one that is close to 0.0. This is common:

The winning class in NB classification

usually has a much larger probability than the other

classes and the estimates diverge very significantly from

the true probabilities. But the

classification decision is based on which class gets the

highest score. It does not matter how accurate the

estimates are. Despite the bad estimates, NB

estimates a

higher probability for ![]() and therefore assigns

and therefore assigns ![]() to the correct class in Table 13.4 . Correct estimation implies

accurate prediction, but accurate prediction does not imply

correct estimation. NB classifiers estimate badly,

but often classify well.

to the correct class in Table 13.4 . Correct estimation implies

accurate prediction, but accurate prediction does not imply

correct estimation. NB classifiers estimate badly,

but often classify well.

Even if it is not the method with the highest accuracy for text, NB has many virtues that make it a strong contender for text classification. It excels if there are many equally important features that jointly contribute to the classification decision. It is also somewhat robust to noise features (as defined in the next section) and concept drift - the gradual change over time of the concept underlying a class like US president from Bill Clinton to George W. Bush (see Section 13.7 ). Classifiers like kNN knn can be carefully tuned to idiosyncratic properties of a particular time period. This will then hurt them when documents in the following time period have slightly different properties.

The Bernoulli model is particularly robust with respect to concept drift. We will see in Figure 13.8 that it can have decent performance when using fewer than a dozen terms. The most important indicators for a class are less likely to change. Thus, a model that only relies on these features is more likely to maintain a certain level of accuracy in concept drift.

NB's main strength is its efficiency: Training and classification can be accomplished with one pass over the data. Because it combines efficiency with good accuracy it is often used as a baseline in text classification research. It is often the method of choice if (i) squeezing out a few extra percentage points of accuracy is not worth the trouble in a text classification application, (ii) a very large amount of training data is available and there is more to be gained from training on a lot of data than using a better classifier on a smaller training set, or (iii) if its robustness to concept drift can be exploited.

| (1) | He moved from London, Ontario, to London, England. | ||

| (2) | He moved from London, England, to London, Ontario. | ||

| (3) | He moved from England to London, Ontario. |

In this book, we discuss NB as a classifier for text. The independence assumptions do not hold for text. However, it can be shown that NB is an optimal classifier (in the sense of minimal error rate on new data) for data where the independence assumptions do hold.